Explore Feuilletons

A City and Mother

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

Copyright holder

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Natan Alterman, “A City and Mother,” 1934. Translated by Amy Asher

A | Point of View

Read Full

The Purim Parade [Adloyada] and the Levant Fair [Yerid ha-mizrakh] are destined to be born twins this year, akin to Esau and Jacob in their day, with the hand of the one grasping his brother’s heel. This adorable twosome is tumbling about in the womb of Mommy Tel Aviv,1 while she, bloated by the impact of her double pregnancy, pale with happiness and wide-eyed with expectation, lies speechless and accepts with a pretty, worn-out smile the dignity she so properly and richly deserves.

Praise to the Mother of the Sons! Do go gentle on her. Take good care and show her courtesy. Stir not up, nor awaken2 the nascent seed of the future!

And all around obey the order, all bow heads and tiptoe. The air becomes ambience and the wind becomes a mood… Gallant knights guard the expectant mother’s bed. The rooftop spears are upright and fixed, the houses – suits of armor – silent and sealed, the heavens hang heavy, full-bodied and clouded, like a dark palace dome, mysteries and cobwebs galore. Only the streets keep flowing like fevered arterial blood, with white bus cells and red bus cells. Only the construction motors pound persistent and tense, as apprehensive hearts, eager for the distinguished day. […]

B | A Private Congress

Meanwhile, as always in the times between holidays, interregnum so to speak, wondrous things are happening here. To see how truly great they are, no need for penetrating eyes, for a discerning mind, or a talent uncommon. It’s enough to go out on the street and wander about, believe that beyond politics and the economy and Hitler worldly wonders do abound, and that a man dipping his feuilletonistic pen in that whirlwind of life, ever gushing, bustling, butterflying in myriad waves and sparkles and flickers of light and darkness, must seem miserable and absurd, a phlegmatic tourist if you will, keen on capturing the Niagara falls with his miserable Kodak… I actually find that comparison slightly offensive. My self-love wears a serious face and announces that it scorns the Niagaras of this world, willing to author a trilogy on Tel Aviv’s past, present and future without sparing a detail, without narrowing its narrative scope by even an inch… And furthermore she adds – my self-love – that if she had the time to study and to fathom and to know, surely she would win first prize for the literary masterpiece and so, and so…

But my heart, who’s mighty kind when upset, snaps with anger and retorts, that first of all there is no time, and plus there’s no reward, and thirdly it doesn’t interest him at all… So he shouts and glances furtively above, towards the tyrant brain, whose custom it is to drench him with cold water, when he is at his most pathetic. This time, however, there is no such fear of a shower. The brain smiles in agreement, with all the wrinkles of its withered face, and decides most sensibly that he who is so fond of swimming in the whirlpool on his own cannot cast the wide net. He must settle for the small fry caught in the flow off-hand, off-eye and off-ear.

I wait for a few moments, to see whether another of the habitual jurors stirs up, whether another sore travail is born to be exercised therewith,3 one far removed from a feuilleton and from Tel Aviv… Perhaps some pallid envoy from the land of memory would seek to open up the archive? Perhaps some insolent desire would rise up and demand the right of speech? But as I see that this time there is no commotion, no outcry or clamor, I wrap my inner congress with a jacket and take it down three floors into the street.

C | An Anonymous Donkey

I always love the street. I feel that had I not been human, I’d like to be a street… That is how much I am fond of it.

The streets consume their lives like candles burning on both ends, like spendthrift millionaires with excess soul and vigor. They die only from 2 to 4 a.m., whereupon their tired roads hang on to the necks of big, fossilized horses, and then everything is shut and sealed by the locks of silence and calm, everything wishes to rest like that, sleep endlessly, until the end… But the eyes of the streetlamps are open wide, agape, bulging out of their sockets, suggesting that the town is waiting with speechless insistence, with cruel and concrete confidence, for the dead to resurrect.

And that resurrection is always one. Pale and anxious, sad and frigid like a criminal sentence. Whoever waits out the night between the shadow and the lamp, or crosses the great distance between one wall and the next, sees her and hears her full well.

The first to raise his voice is the classic cock, that miserable rooster forced to prove day by day that he had indeed been given the understanding to tell night from day4. His lonely call soars upwards like a lucid rocket, rises and perishes, rises and vanishes, until it falls quiet.

Then the silence turns over and resumes its slumber as though nothing has happened. And I feel at this moment that a city clock is lacking here. I remember those clocks staring like cyclopean eyes from municipality towers and the gates of ancient walls in European towns. Rusty, hoarse with age, their musty core storing legends on secret meetings of slender-bodied and slender-minded princesses with lionhearted knights wrapped in black capes. They grind inexorably, incessantly, like venerable exhausted Samsons, the flour of the bittersweet years of the city and the citizens, and at that very moment, after the rooster’s call, within the mightiness of death and oblivion, intensified and deepened sevenfold, they start tolling from somewhere around, or above… Thus: one and one in silver sounds, one and two in copper sounds, one and two and three and four in a heavy sighing iron thud… And all the city’s clocks respond in a medley of sounds, in a multivocal murmur of prayer, to the cantor, the service leader passing before them… So by the time one iron dies, the second silver shall be born, and by the time the first cry snaps, the new laughter shall flourish. Like memory, like regret, like blind caresses of comfort, the bells of time descend on the arising city, overcome by the burden of its days and nights.

In Tel Aviv, however, they are nowhere to be seen. Instead, we have a donkey, who starts pining for someone or other always at the same early morning hour. His tragic asinine voice squeaks like a cello gone insane, whose strings are all wild and whine in unison. He seems to be very lonely and hard at work, with little time to even grumble during the day. It seems that he himself is unaware of the importance of his role, and has no inkling that those whose eyes are open wide just like his so late o’clock lend their ears to him alone, echoing with their taciturn yearnings his own, as much as all those aforementioned clocks that join the first to form a chorus.

Perchance I meet him sometimes on the street, small and wretched and disgraced, laden with bricks, construction sand, or vegetables, unable to tell him from the others of his kind. Why does he always cry incognito? I would like to know where he lives to pay him a visit and thank him. I’d like to get to know that donkey face to face.

D | The Roofs Light Up

After this singsong, nightly darkness can no longer slumber. Nightmares terrify it and its face grows leaden-blue with horror. At this hour, the houses stand pallid and frozen, like frightened children at their sick mother’s bed. Somewhere in the distance the sea also snores his last snorts, and the small, quotidian noisy voices, full of evil and cowardice, rear their heads and grow louder, ever more audacious.

The clinking of wheels and the clopping of hooves break out of their refuge, pounce on one another’s back and roll together down the road.

A shutter, suddenly snapped open, slaps the somnolescent house and disenchants it back to real life.

The sound of hurried footsteps pounds on the pavement… That’s too much. The thumps are too noisy: I cannot see the walking man. It seems to me he is trying his hardest not to sound so loud…

But the lamps have already shut their eyes and dawn can now legally rise. The newspaper vendors, Tel Aviv’s muezzins, start trilling their cantillations. With hurried yawns the doors open wide. Windows who have stared into homes all night long now rub their eyes with feigned innocence, as if they have not seen a thing… And the municipal broom crawls back to its lair with motorized groans like a nocturnal drunkard broken and crushed by debauchery and disgust.

It is then that the roofs start preparing for something. Excited, ablush, they suddenly light up in victory bonfires that spread the news – sun!

Upon this signal the noise breaks all levees and rains down in a tempest – daytime… And right this moment all is forgotten and washed away – the night, the lamps, the silence, the donkey… All ‘till none survives. Only lovely drowsy girls on their way to the workshops and factories still drag behind the balminess of beds and the tatters of their dreams.

E | The End of the Beginning

Immediately the streets start running, in one direction or in two, running and scampering, running and winding, to the sound of voices, to the flash of colors, to the rise of dust clouds and the flicker of road signs. From high above the entire city must seem like a giant carousel, reeling and wobbling and swinging inebriated.

A carousel and a zoo!

Yemenite porters push their wagons, together seeming like a kangaroo carrying her newborns deep in her belly.

The concrete elevators climb like nimble monkeys up the scaffolds of the houses.

The municipal water cars prance like elegant peacocks, flaunting the multicolored splashes of their outstretched tails.

And ravenous automobiles howl as though their intestines are twisting and turning. Oh you concrete jungles!... Many are those who trample your tortuous paths with their feet and talk about Nature as one speaks of a beloved woman’s bosom. Why don’t they hear the rumbling of the asphalt like the wild whisper of savanna grasses? Why don’t they listen in the silence of each roof to the murmur of the treetops in the tempest? The sun sheds its light on city and country alike, the night wraps them both in its blanket and the gale whips them thunder and lightning with complete impartiality. Indeed, the town and field and waterfalls and virgin forests are brothers, born of the same mother Earth. Rapacious civilization has conquered primordial nature or is in the process of doing so, fertilizing fields, damming the cascades, ordering and regimenting tree herds, and it appears that the primeval wildness, the vigor that preceded mankind, the endless war, the merciless law, all those paradoxically linger only in the vast urban sprawl. It seems that man’s love for the city, the birthplace of electricity, machinery and crowds, precisely that love is an odd but ineluctable incarnation of his longing to a primitive life, a life of nature, of unchained loneliness, of animalistic affinity to man and land.

Already Tel Aviv hears the first whistles of this factory of human happiness and grief. The wheels start churning and trampling. The flow of the new masses has accelerated and intensified with huge momentum. Here, molten animated metal simmers in the furnaces, and should the pen so desire, I will cast some of it into the molds of the following chapters.

- “I am one of them that are peaceable and faithful in Israel: thou seekest to destroy a city and a mother in Israel: why wilt thou swallow up the inheritance of the Lord?” (II Samuel 20:19; KJV). ↩

- “I charge you, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, by the roes, and by the hinds of the field, that ye stir not up, nor awake my love, till he please” (Song of Songs 2:7, see also 3:5, 8:4; KJV). ↩

- “And I gave my heart to seek and search out by wisdom concerning all things that are done under heaven: this sore travail hath God given to the sons of man to be exercised therewith” (Ecclesiastes 1:13; KJV). ↩

- “Who gives the ibis wisdom or gives the rooster understanding?” (Job 38:36; NIV). ↩

Commentary

Natan Alterman, “A City and Mother,” 1934. Commentary by Giddon Ticotsky

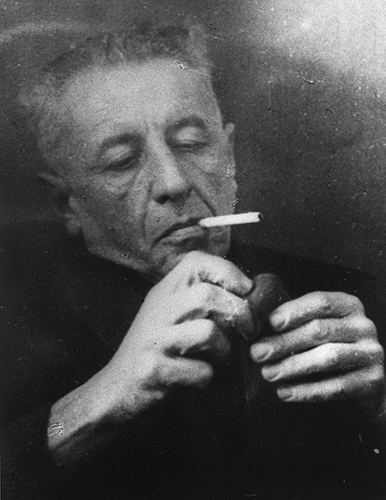

In this text, a young man, a young city, and a young genre come together at a particular historical moment. The man is 23-year-old Nathan Alterman, a few years prior to his resounding debut as a leading modernist Hebrew poet with the publication of Kokhavim ba-chuts (Stars Outside) in 1938. The city is Tel Aviv, founded barely one year before Alterman was born. And the genre is the feuilleton, which by virtue of vacillating between another two—journalism and literature—facilitates irreverence, but always of the gracious kind, out of a constant commitment to entertain. The youthfulness of all three charges the text with energy, with a sense of open horizons and a plethora of opportunities—and moreover, a carnival spirit. Everything still has to be invented: the young city needs to be mythologized, the feuilleton has yet to be established as a more literary and artistic genre, and Alterman still has to find his own creative voice.

“A City and Mother” is the title Alterman chooses for his feuilleton, perhaps innocuously, perhaps sarcastically. The common sense of the original Hebrew phrase—Ir va-em—is a major city, a metropolis. About to celebrate its silver jubilee, and boasting some 34,000 inhabitants, was Tel Aviv a big city? In terms of the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine—certainly yes. But compared to Paris, where Alterman had resided shortly before composing this piece—obviously not. This expression was customarily used to refer to a significant religious Jewish community, typically in the diaspora—very far from the secular and mischievous Tel Aviv portrayed by the poet. The title, moreover, emphasizes the city’s femininity, and is reminiscent of the etymology of metropolis, or “maternal city”. Note, however, that as suggested by Uri S. Cohen, Tel Aviv is less of a mother to Alterman and more of a lover, or perhaps a young sister to be looked after.

Read Full

Less obviously, this text touches upon a fundamental Zionist phenomenon: the metaphor and its concretization. Just as Herzl’s utopia had become reality (albeit partially) in Eretz Israel, so the Hebrew name of his visionary work, Altneuland, as translated by Nahum Sokolov, became the city’s name. In the beginning of Alterman’s work, “A City and Mother” becomes a real-life mother, the biblical Rebecca who parented the twins Esau and Jacob. Immediately afterwards, however, we encounter the opposite phenomenon—a metaphorization of the concrete: “The air becomes ambience and the wind becomes a mood,” and “municipal water cars prance like elegant peacocks.” This constant vacillation from the real to the symbolic and back again is what gives the text its lyrical dimension, perhaps inspired by Baudelaire’s Petits Poèmes en Prose and his flâneur. This double movement also foreshadows Alterman’s turn to neo-symbolism in his poetry, perhaps as a way out of the split between the visionary ideologies then in vogue and the meager reality then in sight: between the European metropolis of his imagination, with its city clock, and the donkey’s monotonous braying in a backwater Middle-Eastern city.

The tension between dream and reality, in terms of the textual content, is related to the feuilleton form itself: “A writer dipping his feuilletonistic pen in that whirlwind of life, ever gushing, bustling, butterflying in myriad waves and sparkles and flickers of light and darkness, must seem miserable and absurd, a phlegmatic tourist if you will, keen on capturing the Niagara Falls with his miserable Kodak…" And all these tensions—between metaphorical and concrete, ideological and real, and perhaps also between life and literature—are defused or at least sidestepped by focusing on the minute, the quotidian, on a “man’s love for the city.”

Further Reading:

- Ruth Kartun-Blum, “Ha-proza ha-shirit: sugim ve-tsurot” [“The Poetic Prose: Genres and Styles”], in Ben ha-nisgav la'ironi: kivunim ve-shinuyey kivun bi-yetsirat Natan Alterman [The Sublime and the Ironic: Lines of Fashioning and Metamorphoses in Alterman's Works] (Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 1983), 77-111.

- Uzi Sahvit, “Alterman ke-gibor tarbut” [“Alterman as a Culture Hero”], in Alterman, meshorer be-ʻiro: meʼah shanah le-huladeto [A Poet in His City: On Alterman's 100th Anniversary], ed. Sara Turel (Tel Aviv: Muzeʼon Erets-Yisraʼel & Merkaz Kip, Tel Aviv University, 2010), 43-51.

- Dan Miron, Parpar min ha-tola'at [From the Worm a Butterfly Emerges: Young Nathan Alterman—His Life and Work] (Ra'anana: The Open University of Israel, 2001), eps. 554-8.

- Uri S. Cohen, “Likrat ha-shira hagdola: ha-proza shel Natan Alterman ha-ts'air” [“Towards the Great Poetry: The Prose Works of Young Natan Alterman”], in Saar u-ferets: proza u-ma’amarim, 1931-1940, eds. Uri S. Cohen & Giddon Ticotsky (Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 2019), 347-77.