Explore Feuilletons

The Bondage of Jews in Spain

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

URI

Keywords

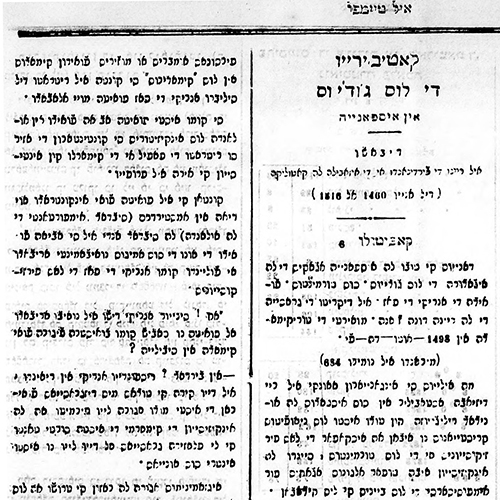

Original Text

Translation

After Adolfo de Castro, “The Bondage of Jews in Spain under the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic (between 1460-1516),” 1875. Translated by Marina Mayorski

Chapter 6

The damages caused to Spain by the expulsion of the Jews — their tournaments — the escape of Enrique de Paz — the decree of grace by the queen Dona Joanna — the death of Tourquemeda in 1498 — Auto-da-fé

The New Christians were fooling themselves, because the king sought to establish religious uniformity. They could not escape persecutions and torture. The Inquisition worked to usurp the property of all those who remained.

Read Full

After the death of Isabella the Catholic in 1504, the New Christians wanted her daughter, the queen Dona Joanna,1 to grant them protection, as she promised in her letter from November 22, 1511: “I pardon you from the punishments you suffered for having opposed the laws of the Inquisition.”

This agreement between the queen and the new converts was nothing but fantasy. As before, the Inquisition did not stop its surveillance of the Jews who opposed its rule. The wood did not cease burning and the judges of the Inquisition continued their infernal work during the reigns of Carlos the Fifth2 and Philip the Second3 with the same force as before.

In 1625 the inquisitors of Seville celebrated an auto-da-fé of burning Manuel Lopez and three women for having conducted business with Jews and for tenaciously refusing to admit their blame. That day, the crowd that accompanied the pitiful spectacle was enormous and the murderers’ camp was so wide that neither people nor carriages or soldiers on horseback could move in the streets.

In another auto-da-fé celebrated in Seville on April 14, 1660, eighty people were burned at the stake, as recounted in the portrayal of the celebrated and elevated poet, Enrique de Paz.4

As the poet fled to Holland, the inquisitors continued to make his effigy from paper and burn it with such intention, as though it was the man himself.

It was told that one day in the city to which he fled, Amsterdam (an important city in Holland), the poet encountered one of his friends who had just arrived, escaping persecution like Enrique de Paz.

“Ah!” – said the new arrival to señor Enrique - “Do you know that your effigy was burned in Seville?”

“Really?” – Enrique responded, laughing – “May it be God’s will that all my misfortunes are of this kind. I permit the Inquisition to burn me in this way, as long as, God willing, I myself am not in their hands.”

We now turn to the reasons for the inquisitors’ abhorrence of Enrique de Paz. Everyone accused him of lighting candles on shabbat evening and conversing with Satan. Enrique, upon hearing these ridiculous rumors, could not help but laugh and make jokes. But one of his friends advised him to flee Spain, where a person’s existence is not assured.

Two days later, Enrique de Paz left for Holland. The Inquisition noted his disappearance and believed that he was in hiding. They searched for him profusely, trying to capture him.

To be continued…

Commentary

After Adolfo de Castro, “The Bondage of Jews in Spain under the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic (between 1460-1516),” 1875. Commentary by Marina Mayorski

The Bondage of Jews in Spain (El kativerio de los judios en Espanya) was serialized in the well-known Ladino newspaper El Tiempo in 1875. El Tiempo was founded in Istanbul in 1872, first as a daily and later appearing 2-3 times a week. It featured primarily news from the Ottoman Empire as well as reports on Jewish affairs across the world, often translated from newspapers in other Jewish and non-Jewish languages. Since its second issue, El Tiempo regularly featured literature – fiction and non-fiction – in a feuilleton section. The location of the feuilleton section varied between the second and the fourth pages of the newspaper, whereas the front page was usually dedicated to news and announcements by the editors. As was often the case in El Tiempo, The Bondage of Jews in Spain was not explicitly identified as a feuilleton, but it appeared on the fourth page, where serialized novels and chronicles appeared before it, and installments ended with the trademark phrase “to be continued.”

Read Full

Published three years into El Tiempo’s operation, The Bondage of Jews in Spain was preceded by a serialized chronicle about the kings and queens of France (Istorya de los reinos de Fransia), and roman-feuilletons translated from French, including stories from One Thousand and One Nights and Bernardin de Saint Pierre’s novel Paul et Virginie. The summer of 1875 marked a shift in El Tiempo’s feuilleton section towards works with overtly Jewish subjects. Such publications included the roman-feuilletons El trezoro de la kehila de York (1875), a translation of a German novel by Eugene Rispart about Jews in medieval England, and Kain (1891), a translation of a Hebrew novel by Nahum Meir Shaykevitsch about crypto-Jews in Portugal. There was also a gradual increase in the serialization of historiographic content. This tendency may have been the result of the wave of historical studies and fiction by German-Jewish authors in the 1840s and 1850s, which were gradually translated to Hebrew and French, two languages that were more accessible to Ladino intellectuals.

The Bondage of Jews in Spain is a genre-bending adaptation of Historia de los judios en España, a detailed account of Jewish history in Spain published in 1847 by renowned Spanish historian Adolfo de Castro (1823-1898). Based on careful and informed studies, including archival research, Castro’s text depicts Jewish life in the Iberian Peninsula from the beginning of Jewish settlement in the region to the nineteenth century. Unlike his predecessors, Castro condemned the Inquisition and the Catholic monarchs, asserting that they merely threw a cloak of Christian piety on ambition and greed. The establishment of the Inquisition, Castro argued, had no objective other than to replenish the rulers’ coffers, exhausted by wars for political and economical dominance in the region. The narrative outlined by Castro was so critical of the Spanish establishment that the author made a point of assuring his readers that he was not of Jewish descent and that his history was written “dispassionately and without craft.”1 It is therefore not surprising that Historia was chosen by the anonymous Ladino translator in the Ottoman Empire.

The sections serialized in El Tiempo comprise the third and fourth chapters of Historia, which deal with the rule of Ferdinand and Isabella in the fifteenth century and the Inquisition’s reign of terror and persecution of converts (or “New Christians”) over the next two centuries. As in the original Spanish text, each Ladino installment begins with a brief list of topics and events that are key to the chapter. But the expansive Spanish text is not simply translated or abridged; rather, the Ladino translator condensed and dramatized selected episodes, transforming the historian’s “dispassionate” account into a historical roman-feuilleton that expands and amplifies the suffering of the Jews and the cruelty of the Spaniards. Discarding many of the text’s scholarly features, the roman-feuilleton replaced parts of the third-person narration with invented dialogue and ended installments with “cliff-hangers.” At times, the Ladino translator intervenes in the text, remarking on the significance of events, highlighting their emotional resonance and commenting on their contemporary relevance.

The efforts of the Ladino translator are exhibited in the installment translated here, which depicts the suffering of the Jewish converts under the Inquisition. Comparing this adaptation to the original text reveals how, even though it originated in a scholarly work of historiography, the historical content is presented in a distinctly literary manner, following the generic conventions of the roman-feuilleton. The installment portrays the rite of “auto-da-fé” (lit. act of faith), the ritual of public condemnation and burning of those considered heretics and apostates by the Inquisition. It also recounts the persecution of Enrique de Paz, the pen name of Antonio Enriquez Gomez (c.1601-c.1661), an army officer turned poet and dramatist who was born to a family of Portuguese conversos. Castro’s text contains several of Paz’s poems in their entirety, as well as the scholar’s interpretation. However, the Ladino feuilleton discards these sections, replacing them with a longer dialogue and an invented account of the poet’s persecution and escape that does not exist in the original. The Ladino text also omits the letters exchanged between Jews who escaped to Rome and those who remained in the Iberian Peninsula, adding instead a dramatic description of the auto-da-fé and the excitement of the Spaniards at the horrific scenes.

The methods used to adapt a scholarly text for El Tiempo’s readers showcase the breadth and flexibility of the feuilleton, a genre that can combine different texts but produce a diverse “whole” that is arguably greater – and certainly more accessible and entertaining – than the sum of its parts. This intriguing text also calls attention to the growing interest in Jewish history as literature, a tendency that will increase in the following decades, with numerous historical novels written in and translated to Ladino. Many of these texts fictionalize the Jewish past in Spain, the ancestral cultural heritage of Ladino-speaking Jews, for whom such narratives could never be just escapist and “easy” reading material.

- Adolfo de Castro, Historia de los Judíos en España (Cadiz: D. Vicente Caruana, 1847), 8. ↩

Further Reading:

- Adolfo de Castro, Historia de los Judíos en España (Cadiz: D. Vicente Caruana, 1847) — The History of the Jews in Spain, trans. Edward D.G.M. Kirwan (London: George Bell, 1851).

Further Reading:

- Rıfat N. Bali (ed.). Jewish Journalism and Press in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey (Istanbul: Libra Kitapçılık ve Yayıncılık, 2016).

- Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Making Jews Modern: The Yiddish and Ladino Press in the Russian and Ottoman Empires (Indiana University Press, 2004).